Demeaning images of the past—Black mammy figures, minstrel toys and more—are reclaimed and repurposed in the art of Betye Saar. In that object-to-art transformation, they’re given a strength that speaks volumes in the present, particularly now as social injustices involving race and gender grab daily headlines.

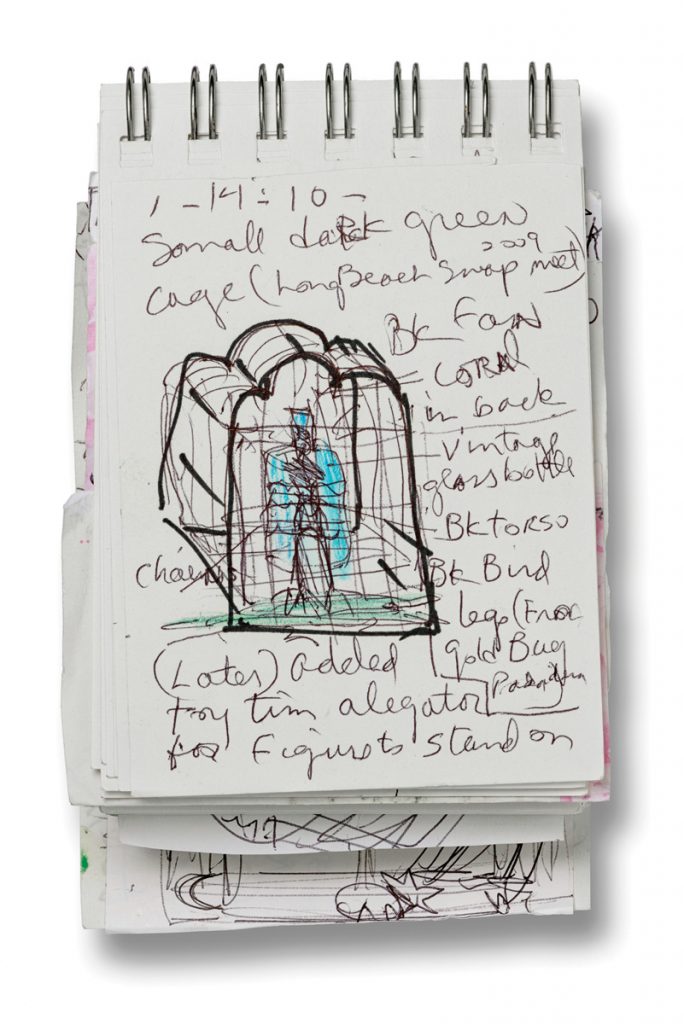

“Betye Saar: Call and Response” is on view through July 11 at the Mississippi Museum of Art. Organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the exhibition is the first time Saar has shared her sketchbooks with the public. Those small drawings, where she toys with found objects and ideas they generate, add an even more intimate feel to the show, offering insights and nudging a closer, longer look at the final assemblages on display nearby.

That “call and response,” with a window into the art’s creation, tightens the narratives’ weave, making them stronger still. Her travel sketchbooks chronicle images and inspirations across multiple continents.

Saar, now in her 90s, is a Los Angeles-based artist known for works that bend and transform derogatory relics and found objects to her own purposes, with results that resonate and provoke. Themes of mysticism and spirituality, family, women’s work, Black power, oppression, heartbreak and hope thread through works that span the arc of her practice from 1970 to 2019.

“Works like ‘Memory Window’ and ‘Eyes of the Beholder’ really give you a sense of where spirituality, gender and race show up within Betye’s world,” Mississippi Museum of Art Chief Curator Ryan Dennis says. “But also, Betye has these early influences by artists like Joseph Cornell and a lot of assemblage artists from southern California—John Outterbridge, Noah Purifoy—working within this period of time” in the late 1960s.

The two-sided collage “Memory Window for Anastacia” summons mystic forces with celestial bodies and heart, palm and eyes motifs on one panel, while the other pays homage to Anastacia, a folk saint venerated in Brazil—a beautiful, enslaved Black woman with blue eyes, an iron collar around her neck and a muzzling mask over her mouth. Copper wires emanate from around the frame, signifying power and energy, “a kind of vibrational frequency connected to spirituality,” Dennis says.

“The way that Carol Eliel, LACMA’s curator who organized this show, describes Saar is that she had three strikes against her: (1) that she’s a Black woman; (2) she’s a woman; and (3) there were not Black women artists working or accepted as artists in the ‘60s.”

Sidetracked away from the art path, Saar studied interior design in college and later returned to study printmaking. “She started getting into the art scene in California and Los Angeles, and through these Black assemblage artists (Outterbridge, Purifoy), really started to develop community,” Dennis says.

Betye Saar’s 2014 mixed-media assemblage “The Weight of Buddha (Contemplating Mother Wit and Street Smarts)” is among several works that reclaim racist relics for the purpose of social commentary. The Eileen Harris Norton Collection. Photo courtesy Mississippi Museum of Art

Spiritual exploration and mysticism were grounding points in Saar’s earlier works, but the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 brought about a shift, with an intentional direction toward more political themes in her art, Dennis says: “Between that and the Watts riots that happened in ‘65, the query for Betye was how to be more involved.”

Angry and upset by the “really horrific and shocking” murder of King, Saar was a mother with young children at the time, and couldn’t walk in the protests, she explains in a short film in the exhibition. “But, I did have a weapon, and that was art,” she says.

Saar’s 1972 “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima,” her first politically explicit assemblage that was part of a Berkeley exhibition about Black heroes, has been hailed as the start of the Black women’s movement. In it, an Aunt Jemima-like figure holds a rifle and a hand grenade, as well as a broom.

Works along that line in this exhibition include “A Call to Arms.” Its assembled mammy figure has bullets for arms, broom bristles for a skirt and a noose around her neck. Behind her, lynched bodies hang in grainy black and white. Black power fists rise from bookending spools—all atop a washboard with an excerpt from Langston Huges across its metal ridges, and tiny rifles nestled in its frame. Domesticity, feminism, direction, power, time and racism all factor into the work that re-employs historically oppressive objects for a subversive new message. “Extreme times call for extreme heroines” is the message trailing across the bottom.

Drawn by the duality in the artwork, Dennis marvels, too, at the power of Saar’s art to inspire and, in a time of oppression against Black folks and Black women, incite a view radically different from the norm. “If you are always seeing this imagery,” she says of the grinning mammy face, “you need something to combat how that’s internalized.”

“Betye is 94 years old, so she’s lived and seen a lot,” Dennis says. In subverting what have become iconic images in American history and used against Black people for ages, “She is really trying to turn those narratives in a different way.

“Once the ‘70s hit, she was in a frame of being more revolutionary within her art, and finding ways to have Black liberation as a practice through her work.”

In one corner of the gallery, a deceptively simple tableau, “I’ll Bend, But I Will Not Break,” becomes more chilling the closer and longer you look. The wooden ironing board frame is imprinted with the well-known diagram of a slave ship’s hold and the Black bodies crammed in there, along with a mammy figure, ironing. The cast iron, shackled and chained to the frame, references female labor, captivity and also the branding irons used to mark and punish enslaved people. The crisp white sheet on a laundry line behind has “KKK” embroidered on it. As a whole, it conveys centuries of oppression and violence against Black people at the hands of whites.

A child’s dress, vintage and fragile, seems rendered even more frail by the ugly harshness of racial epithets sewn onto its skirt in “A Loss of Innocence.”

Another child’s dress becomes a family portrait collage in “Cream,” where youthful innocence seems more intact. Photographs, a lock of hair, tiny butterflies and handprints convey the emotional connection, while a row of buttons in hues from white and beige to brown and black offers a nuanced reference to skin tones.

“Woke Up This Morning, the Blues Was in My Bed” is a metal cot with a blue spirit bottle “mattress” and a swoop of blue neon underneath, all on a bed of coal. Blues lyrics tuck easily into this dark corner, from the slow burn and jagged edges a rocky floor of coal conveys, to the evil spirits a blue bottle bed might keep at bay.

Antique bird cages hold Black bodies captive—a female figure with crow’s feet chained to a bottle and standing on an alligator in one, minstrel waiters and a crow in another cage where padlocks and key chains nearly obscure what’s inside. Fascinating and layered with meaning up close—Jim Crow, discrimination, imprisonment and more—they offer a double punch when you step back, with the haunting shadows they cast on the wall behind.

“The proximity and intimacy of being in this space … they just hold so much weight,” Dennis says of the assemblages. She quotes American studies scholar George Lipsitz’s words on the “Serving Time” assemblage, about descendents of slavery serving time not only in jail, but also locked in low-wage jobs and locked out of upward mobility, and the cages as evidence of their oppressors’ cruelty. Lipsitz is scheduled to give a talk at the museum in Jackson on May 12.

“There are certain details you just won’t pick up on, unless you see it,” Dennis says of the show, encouraging repeat visits to spend time with the exhibition. “It’s very nuanced, and there are a number of connections that Betye is making through these historical images.”

The Mississippi Museum of Art is the third venue to host “Betye Saar: Call and Response,” which also traveled to the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City after its 2019 premiere at LACMA. Through May 23, admission also includes “Piercing the Inner Wall: The Art of Dusti Bongé.” Admission is $15, $13 for seniors and groups of 10+, $10 for college students with school ID, and free for museum members, children ages 5 and younger and on Thursdays for K-12 students. Visit here for COVID-19 guidelines and more information.