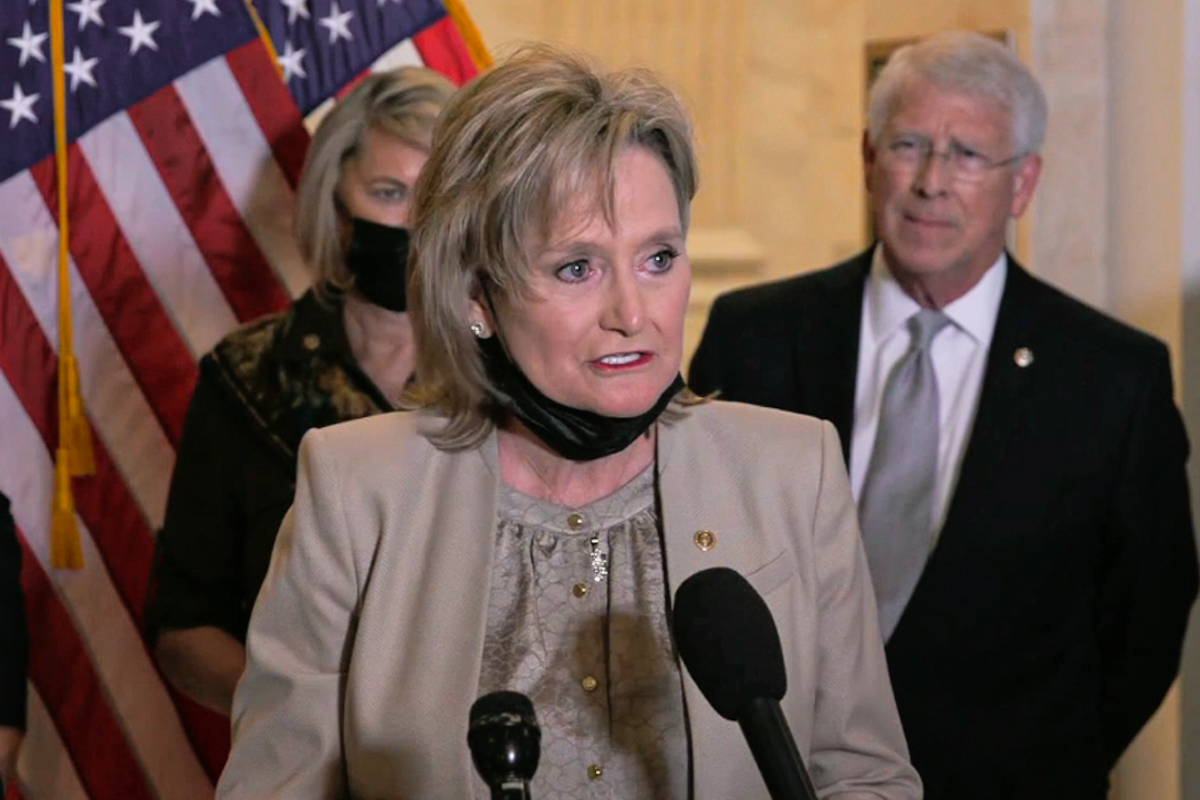

A century after white Mississippi women gained the right to vote, U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith reminded Black Mississippians of feminism’s painful past last week when she insinuated that the For The People Act, a new federal voting rights bill, could diminish women’s gains.

“As a woman in Congress right now, I am the beneficiary of the women who fought for women to have the right to vote. This (bill) would undermine all of this,” Hyde-Smith, the first woman to represent Mississippi in Congress, said at a Republican press conference on March 24.

But the League of Women Voters, a national organization founded in 1920 by suffragettes who fought for their right to vote, supports the bill, also known as H.R. 1 or S. 1. In a statement on March 3, the LWV said the legislation is necessary to “protect” the right to vote, especially for “Black and brown voters,” as lawmakers in states across the country are working on legislation to restrict voting.

Martha Phillips, the director of diversity and inclusion for the Mississippi League of Voters, told the Mississippi Free Press today she considers the senator’s remarks offensive.

“I think her statement is an insult to women and to African Americans, first of all because she doesn’t say how. She simply says that it is and doesn’t say how. We know that the bill enhances the 19th Amendment and the Voting Rights Act of 1965,” Phillips said.

After the U.S. House of Representatives passed the bill, sending it to the U.S. Senate, the national LWV celebrated in a statement on March 4, saying H.R. 1 is necessary to “protect” the right to vote, especially for “Black and brown voters,” as lawmakers in states across the country are working on legislation to restrict voting.

“Passing the For the People Act in the House of Representatives is an important step toward protecting our elections and building a more inclusive democracy,” the LWV said after the U.S. House of Representatives passed H.R. 1. “The League of Women Voters is proud to support this bill that will end partisan and racial gerrymandering, remove dark money from our elections, and restore transparency in our government.”

Sen. Hyde-Smith’s office has not responded to multiple requests for a phone call to discuss her comments since last week.

‘It Was Only For White Women’

Hyde-Smith has often placed herself at odds with feminist groups. In 2018, she used her first Senate floor speech to defend then-Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh after Christine Blasey Ford testified that he once attempted to rape her. Hyde-Smith said she felt “compelled” to do so by her “duty … as the first woman to represent” Mississippi.

After then-candidate Joe Biden selected then-Sen. Kamala Harris as his running mate, Hyde-Smith demurred when asked about the decision’s significance for women. “I would say (if she were) the right woman, this would be a great day. She is not the right woman,” she said.

When this reporter first shared a video of Hyde-Smith’s latest remarks with Arekia Bennett, the young Black director of Mississippi Votes, she initially reacted with bewilderment at the senator’s claim that the bill could infringe on her rights as a woman.

“What? What are you really saying? What do you mean? Did we elect her? That is a scatterbrained response,” the young grassroots organizer said on March 25, echoing the confusion many others expressed on social media when they first heard the senator’s remarks last week.

“If we want to talk about suffragists, that’s part of why H.R. 1 is necessary,” she continued. “Because if you feel like this is going to take away what suffragists did, well, H.R. 1 aims to move past that because it was only for white women when we passed the 19th Amendment.”

Phillips said she thinks the white suffragettes who excluded Black women “were trying to make sure they got what they needed for themselves.”

“And that came as an afterthought to ensure others were included, just as with white men, right? The Constitution didn’t include Black men,” she said. “It didn’t say only white men could vote, but only white men could vote. And I think it’s the same with the 19th Amendment. It didn’t say only white females could vote. It didn’t exclude Black women. People’s behavior excluded Black women.”

‘A Complex Relationship’

After the Civil War, Black men in the South gained the right to vote with the 15th Amendment. While many white women suffragists supported it, the amendment angered others in the movement, especially southern suffragettes. By Reconstruction’s end, however, white state lawmakers had begun implementing racist Jim Crow laws designed to bar Black participation at the ballot box.

“There’s always been a complex relationship between the fight for women’s voting rights and African American voting rights, even before the Civil War, though the abolition movement and the women’s rights movement in many ways overlapped with some of the same people fighting for both causes,” historian Kathryn Tucker, who studies the women’s rights and civil rights movements at Troy University in Alabama, told the Mississippi Free Press.

“With the suffrage movement of the early 1900s, white women were fighting for the right to vote and Black women were fighting for the right to vote. But sometimes there was not welcoming and acceptance for Black women.”

In 1890, the Mississippi Legislature adopted a new state constitution riddled with Jim Crow provisions like literacy tests and poll taxes that effectively rolled back many of the civil-rights gains Black Mississippians had achieved during Reconstruction, including Black men’s voting rights. White southern Democrats feared that Black voters, who overwhelmingly voted for pro-civil rights Republicans in that era, threatened the underpinnings of southern white male supremacy.

“You look at things like Jim Crow and how built into the fabric of America disenfranchisement was, if American voters can’t vote, they certainly can’t elect people and causes that will help them with their situation,” Tucker said. “It’s certainly limiting the voices of the people who can be part of our society and legislation. That was very much the point of Jim Crow.”

In the convention hall where Mississippi lawmakers designed the new 1890 constitution, one state lawmaker, J.H. McGehee from Franklin County, said he would be willing to “sacrifice some of my white children, or my white neighbors or their children” if that was what it took to keep Black Mississippians from voting.

“I will agree that this is a government by the people and for the people, but what people? When this declaration was made by our forefathers, it was for the Anglo-Saxon people. That is what we are here for today—to secure the supremacy of the white race,” he said to thunderous applause.

The 1890 constitution was Mississippi’s fourth since joining the Union in 1817 and, despite significant amendments, remains the constitution in effect today. While the most evident Jim Crow provisions, such as poll taxes, are no more, vestiges remain, such as its felony disenfranchisement sections.

That same year, Women’s Christian Temperance Union President Frances E. Willard, a New Yorker and one of the most powerful women’s rights leaders in the country at the time, explicitly tied her organization’s alcohol prohibition crusade to anti-Black racism.

“’Better whiskey and more of it’ is the rallying cry of great, dark-faced mobs. The safety of (white) women, of childhood, of the home, is menaced in a thousand localities,” Willard, who had previously expressed sympathy for pro-Black activism, told the New York Voice that year as she sought to bring more southerners into the prohibition movement.

The interview, NPR noted in a 2011 story on the women’s rights movement, incensed Ida B. Wells, a Holly Springs, Miss.-born women’s and civil-rights activist whose journalism drew national attention to the epidemic of anti-Black lynchings in the South.

Willard had “unhesitatingly slandered the entire Negro race in order to gain favor with those who are hanging, shooting and burning Negroes alive,” Wells later wrote in her autobiography, “Crusade for Justice.”

Wells, who became Ida B. Wells-Barnett after marrying in 1895, would continue pushing back against white women’s rights activists’ attempts to exclude Black women from their folds late into her life. During a March 1913 suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., she arrived with dozens of other Black women to march with her state’s delegation from Illinois. The event’s white organizers told her that she and the other Black women must march in the back to avoid upsetting southern delegates.

“Either I go with you or not at all,” Wells-Barnett said.

She left for a moment, only to return to march alongside the white members of the Illinois delegation between fellow Illinois suffragists Belle Squires and Virginia Brooks, two white women who supported her defiance. That summer, Wells-Barnett helped ensure the passage of a law in Illinois that gave women there the right to vote in federal and municipal elections.

‘Restricting the Right to Vote Was Part of the Founding’

Wells-Barnett would live to see the 19th Amendment’s ratification—but not the expansion of voting rights to Black southerners. For decades, Black men and women in the South continued to face impossible hurdles to voting like literacy tests. In some cases, white officials would ask Black southerners impossible questions as they attempted to vote, such as, “How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?”

Those difficulties would continue until Congress passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965, which dramatically expanded voting access in the South. It required preclearance from the U.S. Department of Justice before states with a history of Black disenfranchisement, like Mississippi, Alabama or Georgia, could make changes to their election laws.

Those requirements ended in 2013, though, when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the preclearance provision. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, joined by three other liberals on the court, dissented against the ruling.

“Is it the government’s submission that the citizens in the South are more racist than citizens in the North?” U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts asked federal attorneys during the hearings in that case, before declaring in his Shelby County v. Holder decision that, “Our country has changed.”

Since that pivotal decision, freed from the requirements of preclearance, southern states have enacted a flurry of changes to their voting laws with a raft of new restrictions. In Georgia last week, Republican Gov. Brian Kemp signed a bill into law that allows state officials to remove control of elections from counties and from the Georgia secretary of state and gives it to a state board.

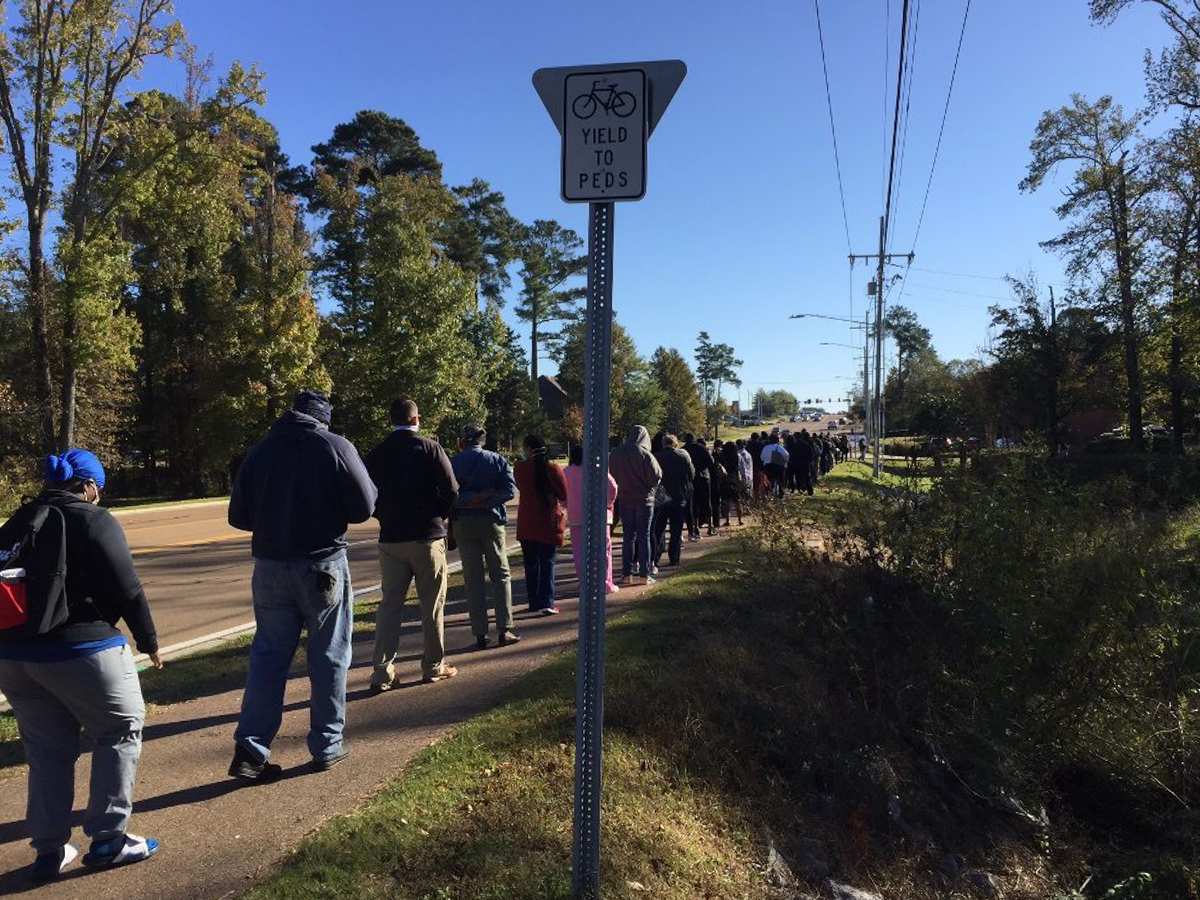

The Georgia law also makes it illegal for anyone to give food or water to people who are standing in line to vote. During the 2020 elections, Georgians who were voting at 90% non-white precincts waited, on average, almost nine times as long as those in 90% white precincts, a Georgia Public Broadcasting/ProPublica analysis found. In some cases, voters waited as long as 10 hours to vote.

The Mississippi Free Press reported on wait time disparities in the Magnolia State, too, when voters in a mostly Black Madison county precinct endured significantly longer wait times than a nearby majority white precinct that local election officials had relocated many of them out of several months prior.

Georgia lawmakers passed last week’s bill after voters turned out in record numbers in November 2020, voting for a Democrat for president for the first time in decades. Georgians then made history in the January U.S. Senate runoffs, when they replaced both the state’s Republican senators with two Democrats, Sens. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff, who made history respectively as the Peach State’s first Black senator and first Jewish senator. Their elections also helped Democrats secure control of the U.S. Senate.

“There are certainly a lot of efforts right now to enact new voting restrictions. Now, as a historian, this is nothing new,” Tucker told the Mississippi Free Press. “Nothing is ever exactly the same as the past, but if you think about all those laws—the literacy tests, the understanding clauses, the poll taxes and the grandfather clauses—in some ways, restricting the right to vote was part of the founding of our nation. Even most white men couldn’t vote if you didn’t have enough money when our nation was founded.

“So this is not new, but neither is the struggle to expand the right to vote. As soon as the nation was founded, women like Abigail Adams were pushing for the right to vote. So this has always been a question in American history as far as who should vote and how they should vote.”

‘It Restores the Voting Rights Act’

Some Mississippi lawmakers introduced legislation this year that would have added new restrictions on voting, but all of those bills have now died in committee.

“We’ve tracked bills that are wild in terms of voter purging, but luckily all of them are dead at this point, but they can resurface at any time,” Bennett, the Mississippi Votes director, told the Mississippi Free Press. “It goes to show you that what happened in November when a record number of Mississippians, including Black or indigenous people who have been marginalized for centuries in this country, turned out to vote. … When this kind of thing happens, there’s almost always an attempt to turn us back to the Jim Crow era and package it as something else.”

Within hours of the Shelby County ruling, then-Mississippi Secretary of State Delbert Hosemann announced that he was immediately implementing the state’s voter ID law, which had been awaiting Justice Department approval after voters adopted it via ballot initiative in 2011. “This chapter is closed,” Hosemann said in an email that day.

Proponents claimed voter ID would prevent voter fraud, while voting-rights groups warned that it could disenfranchise working-class voters and disproportionately affect Black voters, though researchers have reported mixed findings. In a 2019 study, researchers Enrico Cantoni and Vincent Pons reported that they found the requirement had neither reduced fraud nor turnout in states that enacted it.

But during her March 24 speech, Sen. Hyde-Smith said that voter ID had been “successful” in Mississippi and falsely claimed that the For The People Act would “nullify” the state law (it would not). She said that she, as a woman, voted to approve voter ID on her 2011 ballot, and cited an unverifiable story about voter impersonation in her hometown in the 1990s to explain her support for voter ID.

“H.R. 1 doesn’t undo (voter ID). She’s throwing that out there to say it’s going to destroy your world, and it’s not,” Phillips, the Mississippi League of Women Voters leader, told the Mississippi Free Press.

U.S. House Rep. Bennie Thompson, a Black Democrat, is the only member of his party in Congress who voted against H.R. 1 despite originally co-sponsoring it. He told Fox News on March 4 that he opposed it because “my constituents opposed the redistricting portion of the bill as well as the section on public finances.” Thompson represents Mississippi’s 2nd congressional district, which is 67% Black.

If H.R. 1 becomes law, states must create non-partisan redistricting committees that will handle the task of redrawing congressional maps every 10 years after each census. The task currently falls to state legislators. Proponents of the For The People Act warn say their goal is to end partisan redistricting practices.

Republican lawmakers’ decision to continue redrawing Thompson’s district in a way that makes it overwhelmingly African American, as they did in 2012, means his seat is safe for Democrats, but also makes the state’s three majority-white districts less competitive.

The For The People Act would also establish a new public campaign-financing system that would match any small donors’ contribution to a candidate of $200 or less six times over. For example, if a candidate’s supporter donated $100 to the campaign, the public-finance system would match that with a $600 contribution paid for using money from a new 4.75% surcharge on corporate criminal and civil penalty and settlements.

H.R. 1, Phillips said, has “many great things” in it that would enhance Mississippians’ ability to choose their leaders and the direction of their state.

“From the League’s perspective, it gives voters a voice. It restores the Voting Rights Act.”

The federal legislation, Phillips told the Mississippi Free Press, would also make it easier for Mississippians to vote absentee, end Jim Crow-era restrictions that disenfranchise people with past felony convictions (which disproportionately affects Black Mississippians) and allow same-day voter registration for anyone who showed up to vote with an ID.

Some states already allow same-day voter registration, but Mississippians currently must register to vote 30 days before an election in order to participate on Election Day.

Such provisions make voting more accessible to everyone, including women, Phillips said, citing that as another reason she considers Hyde-Smith’s claim that it would “undermine” the work of the suffragettes insulting.

‘I Question Who You Think a Citizen Is’

Within minutes of hearing the senator’s March 24 remarks, Bennett, the Mississippi Votes director, said it reminded her of Hyde-Smith’s most infamous remark: a November 2018 one-liner that many took as a reference to the racist lynchings of Mississippi’s past.

“If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row,” Hyde-Smith said of a supporter during a Tupelo campaign stop, raising much ire and many eyebrows across the country.

Soon after that remark went viral, Hyde-Smith grabbed national headlines again after Bayou Brief published a video showing her talking to supports at a campaign stop in Starkville.

“And then they remind me that there’s a lot of liberal folks in those schools who maybe we don’t want to vote. Maybe we can make it just a little more difficult. And I think that’s a great idea,” she said in the clip, though there is not enough context to know which “schools” she was referencing. Hyde-Smith claimed she was joking.

Despite national backlash over her remarks, she defeated former U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Mike Espy, a Black Democrat, in a runoff several weeks later. Still, Hyde-Smith’s comment angered many of her own Republican voters, and Espy came closer to winning a U.S. Senate than any Black man from the state since Reconstruction.

“If, after you say the most egregious thing I’ve ever heard in my lifetime from any elected official and you still get re-elected with all of that privilege and all of that whiteness, you can then say that H.R. 1 takes away your rights as a citizen, I question who you think a citizen is,” Bennett said. “Because if a white woman like Cindy Hyde-Smith with all of the access in the world is saying she feels discriminated against, it’s really weird to me.”

Many Black Mississippians considered Hyde-Smith’s “public hanging” comment particularly offensive because she represents Mississippi, where white mobs lynched more Black men between Reconstruction and the mid-20th century than in any other state.

The mobs often justified the murders based on false or untested allegations that the lynching victim had raped a white woman. In her publication, “Southern Horrors,” Ida B. Wells described cases in which white women had seduced Black men and later accused them of rape, setting off lynch mobs.

White Women’s Rights Leaders Ignored Lynching

In the 1890s, the divide deepened between Ida B. Wells and some prominent white women’s rights leaders. They and many other American liberals, Wells felt, were not taking lynching seriously or were, in some cases, tacitly endorsing it.

The activist and journalist decided to take her case against lynching to Great Britian in hopes that a people “superior in civilization” could convince Americans to confront southern lynchings.

“Our country remains silent on those continued outrages. It is to the religious and moral sentiment of Great Britain we turn,” Wells said in an 1893 speech there.

The next year, British temperance leader Lady Henry Somersat invited Wells and Willard, the American Women’s Christian Temperance Union president, to speak to supporters of the anti-alcohol movement in England. While sharing a stage with Willard, Wells called out her hypocrisy and that of other white women who used racism to fight for their own rights while turning a blind eye to the lynchings of black southerners.

Wells also pulled out a copy of the 1890 New York Voice interview and read Willard’s own words back to her, including her claim that local bars are “the Negro’s center of power” and that “the colored race multiplies like the locusts of Egypt.”

The Mississippi-born activist was able to garner support for anti-lynching efforts in Great Britian and helped Londoners establish a London Anti-Lynching Committee, which included British religious leaders, members of parliament, scholars and news leaders.

But her performance angered Lady Somersat and Willard, who made her views on Black southern men voting clear in an interview with the Westminster Gazette, a London newspaper, soon after.

“It is not fair that a plantation Negro who can neither read or write should be entrusted with the ballot,” Willard said.

‘It’s Human Behavior’

In her interview with the Mississippi Free Press today, Martha Phillips, the Mississippi League of Women Voters’ diversity and inclusion director, said there is always a risk that our nation’s past transgressions could make a comeback in the form of new voting rights restriction.

The For The People Act, she said, “reminds us and creates an opportunity to enforce” the principle of equality and the need to broaden our democracy’s reach.

Kathryn Tucker, the historian, said she believes that many historians and Americans today see both the Black civil rights movement and the women’s rights movement as ones that “expanded the promise of democracy in the United States, from originally just wealthy white men, to including more people over time.”

“And many people feel that is a goal of American democracy and something to be proud of,” she said.

Phillips similarly pointed to the evolution of American suffrage, from the time when only white male landowners could vote, to 1856, when all white men could vote, to the ratification of the 15th and 19th Amendments.

“And there was never anything for Black women, but then the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act said everyone is equal and everyone can vote,” she said. “What we’re constantly having to do is remind our human nature that we’re equal, and this puts something in place to enforce that.

“We find ourselves here off and on readdressing this. It’s human behavior.”