Victor Hugo Green’s “The Negro Motorist Green Book” was the guidebook for African American roadtrippers during the Jim Crow era. The guide offered services and places that were friendly to African Americans, while also highlighting the dangers of travel with threats such as whites-only sundown towns.

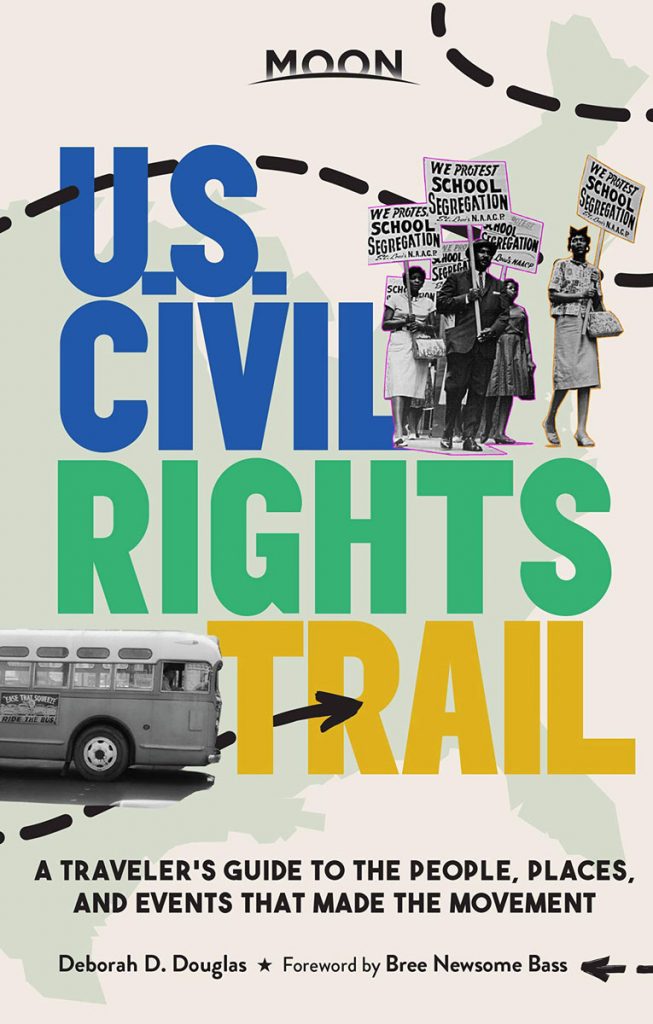

Author and journalist Deborah Douglas is creating her own guide of sorts, this time one through history with her new book, “U.S. Civil Rights Trail: A Traveler’s Guide to the People, Places, Events that Made the Movement.” The self-dubbed “Great Migration baby” takes readers on a journey on the official Civil Rights Trail through what she promises to be illuminative storytelling, historical sites and cultural experiences.

Douglas, a Chicagoan with southern roots, is a graduate of Northwestern University in Illinois, where she also taught and created a graduate investigative journalism capstone on the Civil Rights Act of 1964. At the beginning of her journalism career, she lived in Mississippi and worked at The Clarion-Ledger for almost three years reporting on Madison County, where her family is from.

She was awarded the Studs Terkel Award in 2019, and the Chicago Headline Club has awarded her several Lisagor Awards. She now is the Eugene S. Pulliam Distinguished Visiting Professor of Journalism at DePauw University.

“Black communities and cultural experiences rarely make it into official travel messaging and resources, as they are not often thought of as destinations or must-dos. But they are,” Douglas’ press materials say. She recently spoke to the Mississippi Free Press to explain her goals for the book and the cultural experiences that await on the Movement trail.

Aliyah: I was reading in your bio that you are Chicago born, but southern reared. Can you elaborate?

Douglas: I call myself a Great Migration baby. I was born in Chicago. My parents split early so my mom moved to Detroit, and I started school in post-uprising Detroit, so I started school in a revolutionary environment. My grandparents were from the South. My father’s parents are in Mississippi near Jackson, and my mother was from Tennessee near Memphis. I spent most of junior high school and most of high school in a small town outside of Memphis called Covington. The whole town square, Confederate statue, everything. If you come to my house, I’ll be very nice to you. I’ll be a gracious hostess, but I do have an edge.

Aliyah: What is that edge?

Douglas: That’s that urban edge. The edge that brooks no quarter, and I suffer no fools.

Aliyah: What sparked your interest in history and the Civil Rights Movement? What laid the groundwork for you to begin writing your book?

Douglas: Well, my upbringing laid the foundation for writing this book, and my experience working through structures, matriculating through structures, laid the foundation for this book. Going to public school laid the foundation for the book. Growing up in a Black church laid the foundation for this book and just having questions about why do the states I have lived in function the way they function, why people relate to each other, why is racism either in the day-to-day interactions or in the way that we experience in the United States laid the foundation for this book.

Aliyah: How did those experiences differ depending on where you lived?

Douglas: I’ll say that when I moved to Tennessee for junior high school when I was in seventh grade, I experienced immediate differences in school. In Detroit, I was always encouraged to raise my hand, to participate in class and to speak up. When I went to the South, I could sense that if you were Black or you were a girl that you were invited to silence. Raising my hand and speaking up made me automatically an outlier, but by that time, I had been programmed to participate. To me it’s like programming to participate in democracy. It was more than just school. It was about how are you going to stand in your power in the world?

Aliyah: You mentioned that you were a Great Migration baby. What stories did you hear about that time period? Are there any stories in your family regarding the Great Migration that you can share?

Douglas: I knew there was a reason why my parents and my mother’s siblings moved from the South. I knew they grew up working really hard, that they picked cotton as children. They had to get up really early in the morning and work in the sweltering sun picking cotton just to earn enough money so they could eat that day. It was almost subsistence level existence.

I knew that we lived sequestered in a Black community, and I knew my family relied on the Black church for community, mutual support and aid. And I knew that the whiter world around them was dangerous. I knew that they did not want to stay in the South and be repressed in terms of fully realizing a vision of their lives.

That doesn’t mean that the South is a bad place to be because I don’t want to make it seem like, ‘Oh, the north is so much better.’ It’s just that there was a reason for the Great Migration. People were really tired of being repressed, and they wanted the ability to work and thrive and build families. And to a degree, they were able to do that, come up and take factory jobs. My mother eventually worked her way into the federal government, and my father started his own business. He ran a body shop for a couple of decades, and he hired people who grew up in the South with him.

Aliyah: What time period was this?

Douglas: I was born in 1967, so I grew up in the’ 70s, and I lived in the South in the late 70s, early 80s.

Aliyah: How was it working in Mississippi the three years you were here and being that you reported in a county where your family has a lot of ties?

Douglas: Before I came to Mississippi, I talked to one of my old mentors and they told me to be

aware that Mississippi and this particular paper, The Clarion-Ledger, would be task oriented. They always want you to do things, working all the time as opposed to maybe being able to have time and space to do more enterprise stories. And so they were right. We all worked really hard.

In terms of how Madison County was, it’s really kind of hard. Not being there now, looking on the outside in, I could see the remnants of past racism and understand why Mississippi has the outcomes that it has in terms of indicators like education and economic mobility. I can see that very clearly, but also I thought Mississippi was and is a beautiful place. I always said that when the revolution comes, I want to be in Mississippi because people there know how to do stuff with their hands, and they can rebuild the world. They know how to do things.

Aliyah: When was the last time you have been to Madison?

Douglas: I was there in late 2019.

Aliyah: Seeing how it looks now, how did it look back then when you were reporting there?

Douglas: South Madison County was on the come up then. Mary Hawkins was the mayor of Madison at the time. She’s still the mayor. So Madison was just so pristine, and it was a planned community, really well thought out. Ridgeland was on and popping. I lived off County Line Road for my first apartment. Going towards the reservoir, I had my first po-boy there, and it changed my life. I’m like, how did I not know this sandwich existed?

Aliyah: That’s the one thing you can count on when people come to Mississippi. They are always going to eat well. I’ve never met a person that’s been here and said the food wasn’t good.

Douglas: You won’t get that, either, because the food is good for you. But it’s really great to see the realization of plans that were being discussed. When I was covering Madison County, I covered the nascent beginnings of the Nissan Plant when it was just an idea, and they were just developing that relationship. I covered the development of west Madison County, so to see an idea come to fruition is amazing.

Aliyah: You mentioned that you were waiting for the revolution to happen in Jackson. What do you think will be the catalyst for that to occur, and what do you think that will entail? We have people who are investing in Jackson like Dr. Nashlie Sephus, who bought some acres on both sides of Gallatin Street, and she’s going to develop a tech district.

Douglas: I honestly didn’t speak about it to that degree. I just play around with this idea of a revolution coming, in general, and hadn’t really thought about specifically in terms of Jackson. I read (MFP Editor) Donna Ladd’s piece that she published for NBC News Think this past weekend where she talked about the disinvestment of Jackson and the white flight to the suburbs and the racist, not quite dog-whistle messaging that suggests that Black people can’t run things, and I think she was just spot on.

So, I think we need to have a reckoning with that in Jackson and a lot of other places that I travelled along the way. We can run things, and we helped build this country with our back and our labor. I just think if we can come together and work together, then we can fully realize our potential and Mississippi has a lot of unlocked potential. I just think it hinges upon us coming together and mutual respect and the ability to really celebrate the story that is Mississippi and then move forward.

Aliyah: Moving onto your book, what exactly is the U.S. Civil Rights Trail? Talk a little bit about its history.

Douglas: A collection of southern travel offices got together and designated an official civil rights trail. Various states were telling the story in their own piecemeal way, but they realized they had something really beautiful on their hands, and they could tell a more cohesive narrative by designating the trail and creating a map of the trail.

So, if you go to www.civilrightstrail.com, you’ll see the map is beautiful. It starts as far east as Wilmington, Del., which is the site of the first local government coup in the United States, and it goes as far west as Kansas. It goes deep into Louisiana and Florida. They designated this trail officially in 2018. My goal was to follow this official trail. Writer Charles Cobb has written a civil rights trail in the past. He has seeded the idea of the trail, but this goes along that official trail established by those travel bureaus.

Aliyah: When did you first encounter the trail, and when did you know this was a journey you wanted to embark on?

Douglas: Well, I submitted a proposal to Moon Travel, who had plans to produce a book, and I won the proposal process. I think I submitted in 2018, and I embarked upon my journey the summer of 2019.

Aliyah: Did you get an itinerary together? Did you decide which states you were going to visit?

Douglas: I had to create a cohesive narrative arc of the mid-century Civil Rights Movement because I couldn’t go to every place on the trail. Actually, new spots are being added on a regular basis, so it’s just gotten so much bigger. But I needed to go to enough places to capture the story of the mid-century Civil Rights Movement.

So naturally, I’m going to start with something happening in the 1950s right, Brown v. Board of Education. That means I need to go to Little Rock and then I need to think about cases involved in Brown, which is how I ended up covering Farmville in Virginia. That was one of the five cases involved that made Brown. (It involved) Barbara Johns and the school walk-out that she orchestrated. The looming person in the movement was Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., so I covered his beginning, middle and end. His middle-class upbringing in Atlanta and what was going on in Atlanta. And the fact that he emerges in a powerful way with the Montgomery Bus Boycott and that he perishes in Memphis when he was assassinated.

Those cities are also critical for other reasons. Memphis because Dr. King was there to support a labor movement, which is still the running theme in our discourse. In Atlanta, you have a thriving middle class juxtaposed to the poor people who lived in the Mississippi Delta. You gotta go to the Delta because Emmett Till was murdered there, and his murder was a catalyzing force for the Civil Rights Movement.

I made decisions based on things like that. I went to Charleston because I needed to explain how Black people got here in the first place. Charleston was one of the ports for enslaved Africans. They also made the technology and skill that enslaved Africans brought with them in terms of cultivating rice that made Charleston rich, and that’s a metaphor running throughout the economic story of the United States.

Aliyah: It sounds like a ton of research went into this, so how long was that process? And did you drive or fly?

Douglas: I did a lot of research just to write the proposal to get a sense of how we are telling this story already. I had lots of spreadsheets, so that I could make sure I went to all of the non-negotiable places that needed to appear in this book. As a travel book, I have to curate an experience. So that means not only am I sending people to cultural institutions or historical spots, but I’m sending people to restaurants and nightlife venues to fully engage with the cities as they are today. And in my book, I amplify Black-owned businesses whenever possible unless otherwise specified. In my book, you’re going to a Black-owned business because I feel like that is the best way to invest in these communities and to invest in the story and show respect for the sacrifices that people made in the Civil Rights Movement.

Aliyah: Which states were non-negotiable?

Douglas: Well, non-negotiable places were like I had to go to the Delta, I had to go to Memphis, I had to go to Little Rock, and I had to go to Atlanta.

Aliyah: Did you drive or fly?

Douglas: I did both. I was moving at a fast clip. I just didn’t slow my momentum. I might fly to some place, rent a car and then drive. I flew to Jackson, spent several days in Jackson and then went up into the Delta and spent some time there. I actually sat at my friend’s kitchen table in Jackson and plotted my course with a paper map to go up into the Delta. I double-checked my spreadsheets and I called Senator David Jordan, who is also a councilman in Greenwood, and he was waiting for me on the other end.

So I drove to Greenwood City Hall and had a conversation with him before I embarked upon my journey through the Delta and before I checked into my hotel. He actually attended the trial of the murder of Emmitt Till, so it was just really great to connect with history in such a direct way as soon as I got up there. There was also a flood the week I got there, and a couple of people perished, so I really wanted to make sure I was safe in terms of weather.

Aliyah: How long did you give yourself in each state you visited? Did you know when you had enough information, or did you stay as long as possible?

Douglas: It just depends. I went to places many times.

Aliyah: Which ones in particular were the most surprising to you in terms of learning history that you weren’t aware of? Any person in particular that left a lasting impression or told you any interesting stories?

Douglas: Well, I made a lot of friends along the way. People who are like family to me, like Sybil Jordan Hampton. She was in the second group of students who integrated Little Rock Central High School. It was the Little Rock Nine in 1957. In 1958, they cancelled high school altogether in Little Rock. In 1959, they reintegrated again, and she was the youngest member of the students who integrated Little Rock Central High School. She’s just gone on to have a career in nonprofits and education, and she’s just an amazing woman.

In Birmingham, I got to see Reverend Calvin Woods in action. He and his brother, Abraham, they led sit-ins, and they did other things in the movement. They were members of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights founded by Reverend Fred Lee Shuttlesworth, who looms large in Birmingham. I saw Reverend Woods leading a group of people in a tour at Kelly Ingram Park, which was a staging area for the Birmingham campaign. It’s kitty corner to 16th Street Baptist Church and across from the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

Later, I managed to get some connections and talk to him by phone. I wanted to learn more about what he was doing that day, what he spends his time doing day-to-day and about his role in the movement. And he told me about the founding of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights and about the secret meeting before the official meeting where they founded this group. I started asking for names of people who were at the secret meeting because you know it was dangerous, and he told me to back off. He said don’t nobody need you to know who they were with and where. He was like you need to slow your roll, pretty much. But I just thought it was very poignant that that was a risk back during those times. It was secret then, and it’s a secret now. It was really serious. The stakes were high.

Aliyah: Who else did you encounter in the Mississippi Delta? What places did you visit? What stories did you hear? Did you explore any other areas or parts of Mississippi outside of your itinerary?

Douglas: I had to stay really focused, but people asked me did you go to this museum or did you go to that museum, and I’d say no because that’s not the Civil Rights Movement. It’s some interesting Black history, but it’s not civil rights. I went to every place that is on the official Civil Rights Trail and if I found other places that were linked to the movement, then I added them if they were curated in a way where people could engage in those spaces.

I met Mayor Johnny B. Thomas in Glendora, Mississippi, who runs the Emmett Till Historic Intrepid Center there. His father has a connection to the Emmett Till story. He told me that his father helped dispose of Emmett’s body, and I say Emmett, not Till, because he was a child. I want to make clear that they murdered a child. The museum is the former cotton gin where they got the cotton gin and the barbed wire to wrap around Emmett’s neck.

I met a woman, and her mother had a Supreme Court case in Shaw, Mississippi. I had dinner with her. The case was Hawkins v. The town of Shaw. I didn’t include this in the book because I had to be super tight and focused, and this case was decided in the 1970s. This was a racial discrimination case from the early ’70s. I had dinner with one of the children of this couple that sued the town of Shaw and won at the Supreme Court level. They won the right to access municipal services that their tax dollars were paying for. In Shaw, they weren’t trying to do all that. I had dinner with Gloria Hawkins. I have a picture with her and Dr. Timla Washington, who is a congressional aide for (U.S. Rep.) Bennie Thompson’s office. That’s how I got to meet her.

Aliyah: How was the food in the Delta? What was your favorite meal?

Douglas: It was the ambrosia of the Gods. To me, that is what food is. Well, my favorite soul-food meal is fried chicken, greens, sweet potatoes and cornbread. If you have some macaroni and cheese on the side, that’s good. And my grandmother introduced me to that meal, so anytime I am in Mississippi, I’m really trying to reprise the memory and find some configuration of that meal. Also, I love field peas, and you can’t get field peas any better than the ones in Mississippi.

Aliyah: Do you feel closer to Mississippi after this trip?

Douglas: I actually grew closer to Mississippi when I worked here because my grandmother was in north Madison County, just north of Canton. I lived with her for eight months, so I was just able to connect in a more meaningful way with my grandmother and drill down into family history. I always grew up making quick weekend trips with my dad and his family. I remember once when I was 4 years old, I spent two weeks with her and I got to eat ice cream everyday. Oh my God, it was so much fun. Just to be able to connect with my family and my family’s history and really understand the source of my work ethic, which comes directly from their work ethic. I’m so proud of my family, and I’m so proud of Black people in Mississippi and everything I learned about how they do things.

Aliyah: What impact do you think the book will have on people who have never been to any of these southern states? What impact will it have on broadening their understanding of southern culture?

Douglas: I really hope that it unlocks the beauty of the South. It’s just a beautiful region of the country. We have some problematic attitudes that people are really trying to keep going that need to be destroyed and dismantled. When you push aside all that ugliness, it’s a beautiful place. It’s just rich. The earth is just soft and inviting. It has the best food.

At the heart, there are some really good people in the South. We need to engage with that and be in conversation with one another. I am southern, so I take my identity with me. But people want to pin you to one place, and I decided about five years ago that I’m not doing that anymore. That’s why I say I’m a Great Migration baby, and I claim it all.

Aliyah: What was the last stop on the trail? And after reaching it, how did you feel after a long journey of traveling and talking to people?

Douglas: I don’t remember. There is no “done.” I was finishing my writing in the pandemic, which was very weird. I had to do some follow-up research and follow-up calls, and I had to find people in a pandemic. So, I thought it might be easy to pick up the phone and call a place, but I had to find people at home. That took a different type of flex, to communicate with a level of urgency, but also be able to display a level of empathy, that I do know that everyone is being impacted by the pandemic. I really had to work hard to make my queries a priority and to get people to call me back. And keep calling me back anytime I have questions.

Aliyah: It was great that you were able to make the journey before the pandemic because that could have affected the narrative of the journey with having to socially distance and wear masks where you can’t always understand what people say.

Douglas: It’s value to being there. It’s value to doing things on the phone. It just depends on what part you’re working on.

Aliyah: You mentioned you wrote this during the pandemic. How was it writing this book during the civil unrest surrounding the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and others?

Douglas: As a journalist, you compartmentalize. Deborah Douglas the person is very overly sensitive and I feel everything. When I donned my identity as a journalist, I compartmentalized and focused on the task at hand. I just tried to remember how other people were experiencing life at that moment and tried to engage with them as empathetically as possible. That would be the southern part of me.

Aliyah: Would you say that this guide is as necessary as the Negro Motorist Green Book?

Douglas: I would say my guide is as necessary as the Green Book. I think this book is the travel book equivalent to having an Ebony magazine on your coffee table like back in the day when everyone had that. It’s a go to source. It is more than a travel guide, it is a history book. I have timelines of what was going on specifically in each place, so you really understand at a nuanced level what was going on. It’s a civics primer because by learning about what people did in the movement and how they were thinking about things, then you understand movement strategy. If you want it to be, it can be a road map to activism.

In the back of the book, I have resources, timeline that brings it all the way up to the 2020 Black Lives Matter Movement protest, which was the largest social justice protest in the history of the United States according to the New York Times. I have resources for people you need to read, podcasts you need to listen to. Movies you need to watch or books you need to read. It’s a resource that invites you to engage with again and again and again. It’s not something you sit down and read in one sitting. It’s a book that is a part of a lifestyle. In terms of it being like the Green Book, you’ll notice that I never had a book with the artist who designed the cover. There were different versions that we had to choose from, but we settled on the green that evokes the Green Book. I had a Green Book with me as I was travelling. I tried to find some of those places, but I couldn’t. I kind of feel like this does evoke the Green Book. It has the same intent for engagement, safety and celebration that the Green Book had.

Aliyah: Where can people buy “U.S. Civil Rights Trail: A Traveler’s Guide to the People, Places and Events That Made the Movement”? Where can people find you?

Douglas: Girl, everywhere. You can have the book in a day if you go to Amazon. For those who want to support independent booksellers, they should go to www.bookshop.org. It’s at Barnes and Noble and a lot of other places. If you go to www.moon.com, it’s a whole list of bookstores you can order from. In terms of where you can find me, you can find me at www.debofficially.com and @debofficially is also my social media handle on Instagram and Twitter.

Aliyah: Is there anything else you would like to add?

Douglas: Did I mention that I have playlists in my book that you can listen to on the road? I’m a Great Migration baby and I was always on the road either driving to see my daddy or driving down south to see my grandmas. My family always played music, specifically my aunt Virgi and Uncle Bill would play blues music. So I grew to love blues music through those road trips.

I wanted to provide a soundtrack for this experience because a soundtrack was a part of the mid-century Civil Rights Movement. I choose songs in every chapter that had something to do with equality and specifics of the movement in those cities or that area. For example, I have Phil Ochs who wrote the “Ballad of Medgar Evers” or Nina Simone who performed “Mississippi Gotdamn”. In Birmingham, you have Carlton Reese or the Carlton Reese Choir, which was the choir of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights because Reverend Shuttlesworth really believed that music could be a motivator for people participating in the movement.

Correction: Barbara Johns’ name in the above story was originally misspelled. It is now corrected with our apologies.