Before I confessed and repented, the last fun night I had with my Confederate Battle Flag was in my college dorm room at Harding University in the spring of 1996. I had borrowed my girlfriend’s video camera for a project, and later my roommates and I fell into one of those spontaneous, manic, completely sober dance parties that sometimes beset college students studying late at night. It was rock and boogie, air guitars and my Confederate Battle Flag hanging over my bed.

It was hilarious, and I’m afraid that video is around here somewhere. It’s the kind of video from the last century that could get a liberal canceled in the 2020s.

But I can’t deny it was there and won’t deny it was mine. Then, I would have said it was for southern pride. That was the truth when I was 19, but not for much longer. When I moved in as a freshman, I hung it proudly like many other southern white boys going off to college. And why not? I was among the last-ever students to attend S.D. Lee High School in Columbus where the assistant principal would dress up in a Confederate uniform at homecoming pep rallies.

That flag flew from the monument in front of the Lowndes County Courthouse. It flew literally everywhere over Mississippi. It was defiant. It was state pride, team spirit and religious icon. When a people are as defeated, impoverished and humiliated as the white South thought they were, they cling to the things that give a sense of meaning to the losses and a hope of future glory.

Gospel Flanked by Praise and Worship Music

My sophomore year, I held to the heritage-not-hate heresy when I roomed with a guy from Illinois. We both studied political science, and when he moved in, he hung a giant poster of Abraham Lincoln between his posters of Alice in Chains and Meat Puppets. I hung my Confederate Battle Flag between my posters of Amy Grant and DC Talk. When I was literally facing off against Lincoln and godless, druggy rock-n-roll, my rebel flag was just gospel flanked by praise and worship music.

We took Civil War History together, and the prof divided the class into armies based on our states of origin. Tests and quizzes were battles for points. For exams, I would drape my battle flag over my desk, and I booked the class, trouncing the Yankees. I know from southern pride, but the Holy Spirit was haunting me along the way.

I also majored in ministry at my Church of Christ college. I was baptized at 11 and was preaching by 12. I was a high school Bible Bowl champion and youth ministry intern. I hung out with my Baptist friends after prom. We were good kids, leavening our conversation with scripture references, as natural as carrying my NIV in my backpack everyday.

By the end of high school, something was starting to trouble me. The Bible told me Jesus taught that love for our neighbors is the crux of everything. The plain message was about loving everybody, but the implications are complicated and demanding.

All my life, I just wanted to serve the Lord, but it was striking that we were an all-white church, lived in all-white neighborhoods and ate almost exclusively with all-white Christian friends. In our cultural atmosphere, we received signals that de facto segregation was really alright so long as it wasn’t violent. Or it wasn’t, but we weren’t quite ready for some beloved community. Be patient, son, just wait for another generation to die off.

The Rebel Flag Is Irredeemable

My conversion in college came from some generous teachers and merciful Black friends. I kept learning more about the radical love of the gospel with lessons in justice from some quietly dissenting professors.

One night, I asked an earnest, honest, Black friend down the hall what he thought of my Confederate Battle Flag because I loved and trusted him and wouldn’t dare to hurt him. He told me he didn’t like it and found it offensive and horrible, but he trusted that I didn’t mean anything hateful by it personally. It was his grace to me, mercy for my ignorance, and it was enough to convict me. It became glaringly obvious to me, at last—and I’m not looking for a cookie—that the rebel flag was irredeemable. I could not claim to love the Black people in my life like Jesus would and still bear that symbol that caused so much pain.

So I denounced and renounced it forever. My senior year I ran a qualitative survey of Black students for an anthropology class and had the profound privilege of receiving stories and common insights from my classmates that the Christian white South largely ignored after so-called integration. At a basic level, my Black friends felt tolerated but not included, and welcomed so long as they didn’t make any sudden movements. In my senior year, I received the grace of preaching alongside a Black classmate against racism in our church—my altar call, my confession, confirming my conversion.

I still feel the need to do penance and hope I always will. Back in Mississippi after law school, my wife and I voted to remove the state flag in 2001 (losing then but rejoicing when it came down in 2020). Years later in Montgomery, she and I were involved in the childrens’ ministry at our last Church of Christ. We’d been fighting over plenty of other heresies by then, but we were still welcomed to help with Vacation Bible School.

One summer, a sweet white lady really wanted VBS to be inviting for folks outside our church, and she was inspired to give it a ’50s theme. The 1950s. In Montgomery. We objected. She didn’t understand our concern. She wanted fun sock-hops and poodle skirts and was not at all pleased when I asked if we were going to have colored drinking fountains and restrooms.

We lost that vote too, so we got ready to march back to the 1950s. My concession was being asked to preach for the adults on Wednesday night’s prayer meeting. As part of the festivities, the church erected a huge canvas tent on the front lawn. It had a certain style and atmosphere, and I revelled in the anachronistic opportunity to preach under a big tent on a sweltering summer night.

Deliverance from False Prophets

My mission was to preach about the Montgomery Bus Boycott which E.D. Nixon, Fred Gray, Dr. Dr. King and others organized after Rosa Parks stared down the white-supremacist monster in 1955. I knew many of the old folks in the tent were around during the Movement, but I didn’t know where they stood, then or now.

I framed the story as a Christian movement for righteousness, undergirded by scripture and prayer, which it was. Dr. King was a preacher and pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, and he wasn’t pretending. Sometimes white conservatives feel like the Civil Rights Movement was some commie, secular affront to traditional values, and sometimes secular white liberals are skittish to acknowledge that it was a profoundly Christian action, especially for the folks in Montgomery.

We lauded the story of Christians in Montgomery rising in prayer and sacrifice, martyrs risking lives and fortunes, prophets speaking truth to wicked kings, to create a world that better reflects the imperatives of love, justice, and the image of God stamped on every heart.

They fought against outright evil, but I pulled my punches in identifying the villains too specifically from the pulpit. I wanted to keep the audience in the fold as long as I could before they got mad. Many Americans like to forget that the great struggles for justice in America are against Americans; we laud the heroes in retrospect and pretend like they were fighting against shadowy strangers we’ve never met.

The great heresy that binds many white southerners is that the South is nothing more or less than the Confederacy itself. That doctrine comes from false prophets desperate to protect their idols on courthouse squares all over Dixie. Satan has carried too many white folks to the mountain and lied to them that their honor and prosperity depended on the subjugation of black people as some kind of reward for the Lost Cause, as if they deserved to rebuild the walls after returning from Reconstruction exile.

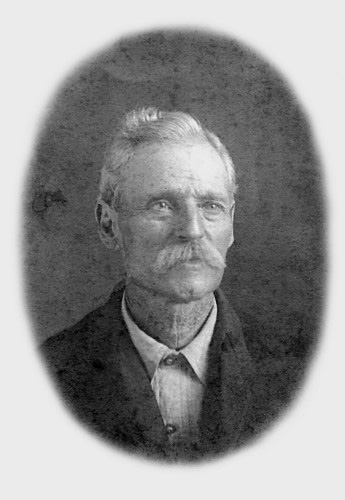

It’s a hard teaching, especially if our ancestors staked their lives on the Confederate cause, like mine did. My great-great-great grandfather, Seaborn Thornton, was a proud private in the Confederacy’s 59th Alabama Infantry Regiment, wounded and captured at Petersburg, imprisoned for the duration at Point Lookout. He wrote in 1901, “I have never regretted that I offered my services and did all that I could in defences (sic) of my Country and our beautiful flag, which though furled, I love it yet. (sic) I have tried to impress on the minds of my children that the Southern Soldiers were not traitors, but that the North was waging upon us a War of attempted Subjugation.”

Seaborn had his reasons, but it is not a betrayal now to recognize the moral imperative of racial justice and redemption nearly 160 years after the bloody war. It’s necessary to reckon with the terror unleashed under that unfurled flag since Reconstruction and the horrors of white supremacy for which it stands.

Along countless Damascus Roads, we find grace and mercy that can deliver us from those false prophets. The South is infinitely more holy and righteous than tattered rags on the twitching Confederate corpse. But until those scales fall from our eyes, we can only see it as through a dark glass. The light may blind us for a while; that kind of grace hurts like hell. But it will excise the sin of white supremacy and its fundamentalist trappings.

When we see the light, we’re left with faith, hope, and love, and love is the greatest of all.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.